Alternative Lending: Big Government and Big Data

May 7, 2014– Professor Michael Barr at LendIt 2014

One of the clear themes of the LendIt 2014 conference was that borrowers are willing to pay extra for speed and convenience. Regulators have taken note of this trend but they’re still supportive of the alternative lending phenomenon anyway. Truth be told, the government is acting like a weight has been lifted off its shoulders. Ever since the 2008 financial crisis, the feds have prodded banks to lend more, but they’ve barely budged, especially with small businesses. Non-bank lenders have relieved them of the stress and all they need do now is make sure everybody plays nice.

One of the clear themes of the LendIt 2014 conference was that borrowers are willing to pay extra for speed and convenience. Regulators have taken note of this trend but they’re still supportive of the alternative lending phenomenon anyway. Truth be told, the government is acting like a weight has been lifted off its shoulders. Ever since the 2008 financial crisis, the feds have prodded banks to lend more, but they’ve barely budged, especially with small businesses. Non-bank lenders have relieved them of the stress and all they need do now is make sure everybody plays nice.

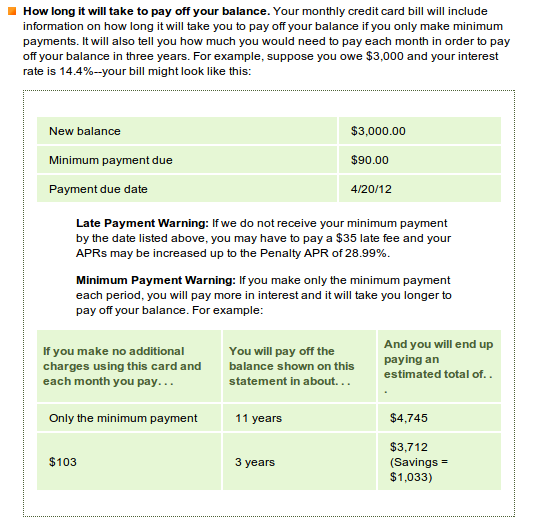

Professor Michael Barr, a former US Treasury official, key architect of the Dodd-Frank Act, and Rhodes Scholar, believes the best way forward is to empower consumers. That’s something lenders can accomplish through education and transparency. On transparency, he cited many of the commendable practices that credit card companies and mortgage companies have implemented, but did not fail to note that these were forcibly instituted through regulation (Hint hint…).

When a LendIt attendee asked Barr to name someone in the alternative lending industry that is a great role model for transparency, Barr answered by saying, “I haven’t seen anyone in the industry doing things the way I would do them in regards to education and disclosure.” On the path towards transparency, “the potential is not yet realized,” he added.

While it sounded as if he favored eventual regulation of alternative lending, he offered all in attendance advice to prevent it. “Take the high road to prevent regulatory interest,” he said.

Barr’s sobering presentation also covered the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the role they might play in alternative lending, if any. Payday lenders and debt collectors were their primary supervisory targets he said, but added the “the CFPB has the flexibility in the marketplace to address problems before they occur.” That flexibility essentially gives them jurisdiction over whatever they decide they want to be in their jurisdiction.

Sophie Raseman, the Director of Smart Disclosure in the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Consumer Policy appealed to the industry in a different manner. “Small businesses are at the heart of the economy. We want to serve you [alternative lenders] better so that we can better serve them,” Raseman pleaded. As part of that, she came bearing gifts, a reminder that the federal government had loads of data available via APIs at http://finance.data.gov. The government wants to make sure we have access to as many tools as possible, most likely to help drive borrowing costs down. If you need to verify someone’s income, Raseman recommended the IRS’s Income Verification Express Service.

The Income Verification Express Service program is used by mortgage lenders and others within the financial community to confirm the income of a borrower during the processing of a loan application. The IRS provides return transcript, W-2 transcript and 1099 transcript information generally within 2 business days (business day equals 6 a.m. to 2 p.m. local IVES site time) to a third party with the consent of the taxpayer.

The irony with this service is the two business day timeline, though I haven’t confirmed if that’s still the case. Delays and archaic data aggregation methods are the exact things alternative lenders are trying to overcome. Kabbage comes to mind as the length of time it takes for them to go from application to funding can be as quick as 7 minutes, a time frame I found to be reality after watching the demonstration by Kabbage’s COO, Kathryn Petralia.

Kababge’s blazing speed is made possible by access to big data, which made Petralia an excellent choice to have on the Big Data Credit Decisioning Panel. She was joined by Noah Breslow of OnDeck Capital, Jeff Stewart of Lenddo, and Paul Gu of Upstart.

Stewart, whose company lends internationally presented the idea of mining not just data on social networks, but the photographs on them. One possibility was measuring whether or not borrowers appeared in photographs with other borrowers known to be bad, or whether or not they hung out with undesirables such as ex-convicts. He was a big believer in association risk, speculating that friends of bad borrowers also made them more likely to be bad borrowers themselves.

Breslow of course said you have to be careful with the noise of social media as there can be a lot of false signals. Does that mean there are big data problems then? Upstart’s Paul Gu said, “we have small data problems” in reference to why there seems to be so much trouble evaluating applicants that have little to no credit history. Gu believes that basic information such as where a borrower went to college, their major, and their grades can be used as an accurate predictor of payment performance and his company has acquired the data to back that up.

Breslow of course said you have to be careful with the noise of social media as there can be a lot of false signals. Does that mean there are big data problems then? Upstart’s Paul Gu said, “we have small data problems” in reference to why there seems to be so much trouble evaluating applicants that have little to no credit history. Gu believes that basic information such as where a borrower went to college, their major, and their grades can be used as an accurate predictor of payment performance and his company has acquired the data to back that up.

Somewhere along in the discussion though the meaning of automation got twisted. OnDeck for instance has an automated process, yet humans play a role in 30% of the loan decision making. Does that mean they are not actually automated? Breslow clarified that aggregating data from many different sources using APIs and computers was automation and that there was still a role for humans. The goal is to make sure that humans aren’t doing the same things that the computers are doing.

“The world’s greatest chess human can beat the world’s greatest chess algorithm,” said Lenddo’s Stewart. “Humans should be pulling what the algorithms can’t think of,” added Breslow. He presented an example of an applicant satisfying all of an algorithm’s criteria but sending up a red flag at the human level. “Why would the owner of a New York restaurant live in California?” Breslow asked. That’s something an algorithm might get confused about. It might mean nothing or it might mean something.

“The world’s greatest chess human can beat the world’s greatest chess algorithm,” said Lenddo’s Stewart. “Humans should be pulling what the algorithms can’t think of,” added Breslow. He presented an example of an applicant satisfying all of an algorithm’s criteria but sending up a red flag at the human level. “Why would the owner of a New York restaurant live in California?” Breslow asked. That’s something an algorithm might get confused about. It might mean nothing or it might mean something.

“Algorithms are probabilistic,” Stewart reminded the audience. They spell out the likelihood of repayment, they don’t guarantee it.

For Kabbage, algorithms and automation have been instrumental in allowing them to scale. “I don’t need to hire a lot more people to serve a lot more customers,” Petralia explained.

“Let the data speak for itself,” Breslow proclaimed. And there is a lot of statistically interesting data. “People with middle names perform better than people without them,” added Breslow.

For Gu, borrowers with degrees in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics fare better than their academic peers, though he wouldn’t reveal which major is #1. That information, while probably available to OnDeck, likely plays little or no role. “There is a lot more data to analyze on the business side than the consumer side which is why [things like] the social graph is a little less relevant,” Breslow said.

In the end, lenders don’t need to go on a wild data goose chase to learn all about their prospective clients. Kabbage applicants for instance are asked to provide their online banking credentials in the very first step of the applications. “A lot of people would be surprised as to the amount of data borrowers are willing to share,” Petralia proclaimed. Indeed, many alternative business lenders and merchant cash advance companies are analyzing historical cash flow activity using third party aggregating services like Yodlee, something that requires the client’s credentials.

During Kabbage’s earlier demonstration, some members in the audience worried that factors such as deposit activity could be gamed. Petralia assured them that their algorithm was sophisticated enough to detect manipulation and at the same time explained that they analyzed far more than just deposit and balance history.

Perhaps all this technology though has gone overboard. Is it possible to predict performance just based on what the applicant says? Believe it or not, “the language someone uses is an indicator of default probability,” Stewart said. But even that kind of detection has become automated. “Lenddo uses semantic analysis. People tend to use different words when they’re desperate.”

Who knows, a year from now getting a loan might be as easy as picking up your phone and saying, “Siri, send money.” Just make sure to delete all the photos of you hanging out with criminals off your phone first. A lender might use them against you.

Merchant Cash Advance Term Used Before Congress

December 18, 2013 I’d like to think that the term, merchant cash advance, is mainstream enough that a congressman would know what it was. I have no idea if that’s the case though. What I do know is that Renaud Laplanche, the CEO of Lending Club gave testimony before the Committee on Small Business of the United States House of Representatives on December 5, 2013.

I’d like to think that the term, merchant cash advance, is mainstream enough that a congressman would know what it was. I have no idea if that’s the case though. What I do know is that Renaud Laplanche, the CEO of Lending Club gave testimony before the Committee on Small Business of the United States House of Representatives on December 5, 2013.

Watch:

In it, he argued that small businesses have insufficient access to capital and that the situation is getting worse. We knew that already. However, he went on to explain that alternative sources such as merchant cash advance companies are the fastest growing segment of the SMB loan market, but issued caution that some of them are not as transparent about their costs as they could be.

The big takeaway here is that he didn’t say they are charging too much, but rather that some business owners may not understand the true cost. I often defend the high costs charged in the merchant cash advance industry, but I’ll acknowledge that historically there have been a few companies that have been weak in the disclosure department. That said, the industry as a whole has matured a lot and there is a lot less confusion about how these financial products work.

Typically in the context Laplanche used, transparency is code for “please put a big box on your contract that states the specific Annual Percentage Rate” of the deal. That’s good advice for a lender and in many cases the law, but for transactions that explicitly are not loans, filling in a number to make people feel good would be a mistake and probably jeopardize the sale transaction itself. If I went to Best Buy and paid $2,000 in advance for a $3,000 Sony big screen TV that would be shipped to me in 3 months when it comes out, should I have to disclose to Best Buy that the 50% discount for pre-ordering 3 months in advance is equivalent to them paying 200% APR?

This is what happened: I advanced them $2,000 in return for a $3,000 piece of merchandise at a later date.

I got a discount on my purchase and they got cash upfront to use as they see fit. Follow me?

Now instead of buying a TV, I give Best Buy $2,000 today and in return am buying $3,000 worth of future proceeds they make from selling TVs. That’s buying future proceeds at a discounted price and paying for them today. As people buy TVs from the store, I’ll get a small % of each sale until I get the $3,000 I purchased. If a TV buying frenzy occurs, it could take me 6 months to get the $3,000 that I bought. But if the Sony models are defective and hardly anyone is buying TVs, it could take me 18 months until i get the $3,000 back.

In the first situation, if the TV never ships I get my $2,000 back. In the second situation if the TV sales never happen, I don’t get the 3 grand or the 2 grand. I’ll just have to live with whatever I got back up until the point the TV sales stopped, even if that number is a big fat ZERO.

Best Buy is worse off in the first situation, but critics pounce on the 2nd situation. APR, it’s not fair! Transparency, high rate, etc.

Imagine if every retailer that ever had a 30% off sale or half price sale one day woke up and realized the sale they had was too expensive and not transparent enough for them to understand what they were doing. If only consumers had given the cashiers a receipt of their own that explained that they would actually only be getting half the money because of their 50% off sale, then perhaps the store owners would have reconsidered the whole thing. 50% off over the course of 1 day?! My God, that’s practically like paying 18,250% interest!!!

To argue that a business owner might not understand what it means to sell something for a discount is like saying that a food critic has no idea what a mouth is used for.

I will acknowledge that issues could potentially occur if an unscrupulous company marketed their purchase of future sales as if it were a loan. That could lead to confusion as to what the withholding % represents and why it was not reported to credit bureaus. I’m all in favor of increasing the transparency of purchases as purchases and loans as loans, but let’s not go calling purchases, loans. Americans should understand what it means to buy something or sell something. Macy’s knows what they’re doing when they have a Black Friday Sale. They do a lot of business at less than retail price. They are happy with the result or disappointed with it. They’re business people engaged in business. End of the story.

In recent years, the term, merchant cash advance, has become synonymous with short term business financing, whether by way of selling future revenues or lending. When testimony was entered that many merchant cash advance providers charge annual percentage rates in excess of 40%, I do hope that Laplanche was speaking only about transactions that are actually loans. As for any fees outside of the core transaction, those should be clear as day for both purchases and loans. I think many companies are doing a good job with disclosure on that end already.

Part 2

The other case that Laplanche made was brilliant. Underwriting businesses is more expensive than it is to underwrite consumers. Consumer loan? Easy, check the FICO score and call it a day. That methodology doesn’t even come close to working with businesses. He stated:

These figures show that absolute loan performance is not the main issue of declining SMB loan issuances; we believe a larger part of the issue lies in high underwriting costs. SMBs are a heterogeneous group and therefore the underwriting and processing of these loans is not as cost efficient as underwriting consumers, a more homogenous population. Business loan underwriting requires an understanding of the business plan and financials and interviews with management that result in higher underwriting costs, which make smaller loans (under $1M and especially under $250k) less attractive to lenders.

Read the full transcript:

LendingClub CEO Renaud Laplanche Testimony For House Committee On Small Business

Merchant Cash Advance just echoed through the halls of Capitol Hill. And so it’s become just a little bit more mainstream, perhaps too maninstream.

Thoughts?

Alternative Lending: People are Finally Getting it

September 12, 2013 Alternative lending is all the rage these days and so much so that BusinessWeek asked the question: What Do Small Businesses Need Banks for Anyway?. They go on to name many companies with ties to the merchant cash advance industry, which is no surprise to us of course. It is interesting however to notice that the mainstream media is not only giving us the time of the day, but starting to treat us like royalty.

Alternative lending is all the rage these days and so much so that BusinessWeek asked the question: What Do Small Businesses Need Banks for Anyway?. They go on to name many companies with ties to the merchant cash advance industry, which is no surprise to us of course. It is interesting however to notice that the mainstream media is not only giving us the time of the day, but starting to treat us like royalty.

Five and a half years ago this very same collective of lenders were referred to as bottom feeding vampires¹. Over the next couple years they upgraded us to a very expensive alternative, then to an acceptable alternative, and now finally to who the hell needs banks when you have these great companies?!. You have to laugh just a little bit at the shift.

It’s easy to call a lender that charges high rates a bad seed when you have no sense of the context. The reality in lending is that a material amount of borrowers don’t make their payments on time or they don’t pay back the loan at all. That causes rates to go up to compensate for the losses. Critics argue that borrowers can’t make the payments or default because the rates were too high to begin with. Some lenders cave to that assumption and position themselves as a fair lender by undercutting the market rates. They eventually learn that defaults are less related to the cost of the loan and more so tied to a borrower’s willingness to repay or ability to repay. Meaning, loans with no interest tacked on to the principle will still be rocked by late payers and defaults. Wait, seriously?

Yes, welcome to America where sometimes borrowers face circumstances beyond their control or they maliciously decide they don’t want to pay. The overwhelming majority are in the former camp, the ones where sudden or gradual hardship is interfering with their ability to make good on their commitment. I admit, even I feel uncomfortable mentioning this. Nobody wants to be seen as picking on borrowers. We’d all rather pretend that lenders are inherently bad and borrowers are inherently innocent. The truth is that most lenders and borrowers are good but some lenders and borrowers are bad. Lending is a two way street and what’s fair for all is somewhere in the middle.

My friends in the commercial banking sector tell me their tolerance for bad debt is less than 1%. Even 1 single loan default over the course of a year could cause their entire portfolio performance to come crumbling down. They do make loans, but they’re often in the tens of millions or hundreds of millions of dollars and only to large established businesses that quite often, don’t even need the capital but would rather not jeopardize their liquidity by spending their own cash. Some of these loans end up getting classified as small business loans even though there’s nothing small business about them.

Mom and pop shops see the statistics and the corresponding rates of say 4% to 10% APR and set that as the bar to shoot for. Then they head down to their local bank and hit a roadblock. The average small retail/food service business is going to have a greater than 1% chance of default no matter how good it looks on paper. I mean think about it, what are the odds that things will go 99% as planned for a restaurant over the next 12 months? Do you think it’s reasonable to assume there is at least a 5% chance that any of the following could happen in the next year even without knowing anything specific? A failed health inspection, bad reviews published online, a revoked liquor license, construction outside impeding pedestrian traffic, internal damage caused by a flood or disaster, extreme weather hurting sales, major job losses in the area leading to people having lower disposable income, key employees quitting, theft, landlord not renewing the lease, competitor opening up in the neighborhood, or declining sales for no single identifiable reason? Lending money to retail businesses is risky, really risky. Suppose the above business owner had a history of late payments and defaults to begin with. At what cost does it begin to make sense to do this deal? And those are just the risks of what could happen to the business itself, so what about the other risks involved?

To a bank, the stereotypical entrepreneur is damaged goods. The hard knock humble beginnings of turning a vision into a successful business usually comes with personal financial sacrifice and in turn a lower credit score. And just as the successful entrepreneur is getting ready to explain his/her high debt to income ratio and story of triumph, they’re already being declined. Banks don’t care about the story. They care about the aggregate mathematics. If there’s just a 5% chance that the business isn’t going to be where it thinks it will be in a year from now, then the deal’s probably a non-starter. Leveraged? Declined. Poor credit? Declined. Business is running smoothly? Who cares, it’s declined already!

Extension on your taxes? Declined. Showing modest profit or a loss for tax purposes ::wink wink:: ? Declined. Didn’t file a tax return? Declined. Co-mingling funds with your personal finances? Declined. Overdrafts or NSFs? Declined. Unaudited financials? Declined. No collateral? Declined. Doing the books with paper and pen? Declined. Have less than 5 employees? Declined. Can’t find a document the bank wants? Declined. Need the money really badly? Declined. Experiencing a downturn? Declined. Have a tax lien? Declined. Have a criminal record? Declined.

Extension on your taxes? Declined. Showing modest profit or a loss for tax purposes ::wink wink:: ? Declined. Didn’t file a tax return? Declined. Co-mingling funds with your personal finances? Declined. Overdrafts or NSFs? Declined. Unaudited financials? Declined. No collateral? Declined. Doing the books with paper and pen? Declined. Have less than 5 employees? Declined. Can’t find a document the bank wants? Declined. Need the money really badly? Declined. Experiencing a downturn? Declined. Have a tax lien? Declined. Have a criminal record? Declined.

Get the picture? If you take a look at Lending Club, an alternative lender, they’re widely known to have a 90% decline rate. Their maximum interest rate is 29.99% APR. Think about that for a second. Some people would say, “WOW, 30% are you kidding me?” but statistically, Lending Club would be losing money on the deal 9 times out of 10 if they approved every single person that applied. Lending Club actually used to be more liberal with their approvals when they first started and what happened is that too many borrowers just didn’t pay. If you believe that Lending Club should approve even more loan applications than they already do, then they would have to compensate for the increased risk and we’d quickly see APRs reach well into the 40s,50s,and 60s.

A critic might argue that once an applicant exceeds the risk of a 30% APR loan, they probably shouldn’t be getting a loan from anyone. That’s not a bad suggestion and what happened is that when the lending world concurred with that 5 years ago, Americans and politicians went up in arms because “Banks weren’t lending.” No loans? Businesses can’t hire. No loans? Businesses can’t grow. No loans? Economy gets stuck in neutral. The nation demanded that capital flow despite the risks presented to the lenders. And so the finance world heeded the call to provide solutions and came up with a smorgasbord of financial products. Merchant Cash Advance financing was already established but had an especially unique characteristic that allowed it to take off. It structured financing as a sale, not a loan. A big problem was that traditional lenders and alternative lenders were at the mercy of state regulated interest rate caps. Once an applicant reached a certain risk threshold, they just couldn’t do the deal anymore. But when financial companies came in to buy future revenues in exchange for a large chunk of cash upfront, the system started to gain some traction.

The effective cost of the money got high, very high, yet they weren’t predatory. I say that because despite how expensive it seemed, most of them were getting eaten alive by defaults. From 2008 – 2010, many merchant cash advance companies filed for bankruptcy. One of the main attributes of a predatory lender is for the lender to actually be getting filthy rich. That means layering on interest way in excess of a healthy profit. Losing a lot of money to help borrowers and small businesses when no one else will can hardly describe a predatory lender.

One has to wonder that perhaps there is a better way. If unsecured financing breeds high defaults, then surely things would be different if a risky applicant secures the loan with collateral. Have the borrower put skin in the game and we’d have a different outcome right? Lenders such as Borro publicly describe their default rate as falling between 8-10%. They offer collateralized personal loans and are described as a “pawn shop for the posh” in the below video, though most of their clients are small business owners. This tells me that even in the instance where borrowers have something very valuable to lose, a significant percentage of them will not repay the loan in full regardless.

A look around at what merchant cash advance companies have been willing to admit has put their average bad debt between 2-5%. In my experience in this industry however, 8% – 15% is a lot more realistic. But are these funding companies getting filthy rich or treading water? Anyone can look at the financial statements of IOU Central², a lender that’s part of the broader merchant cash advance industry. Since they’re owned by a publicly traded company in Canada, we get to see firsthand that they’re suffering tremendous losses quarter after quarter. I find that to be perfectly in line with what I suggested about undercutting the market earlier. IOU Central’s allure is that their loans cost less than a traditional merchant cash advance. The end result is that after paying commissions to sales agents, paying interest on their capital, and factoring in bad debt, they’re hurting pretty badly.

On Deck Capital too, a company mentioned in the BusinessWeek article above acknowledges that they are not profitable, though they do not make their financials public to verify how unprofitable they are or if that’s really even the case.

An SBA loan through a bank may cost approximately 5.5% APR, but if the loan goes bad, the SBA covers almost all of the bank’s losses. There is no such security blanket in the real private sector. The market determines the rates based on the risk. Each funder measures risk differently and in 2013, there is no longer a one-size-fits-all cost of unsecured funding much like there was in 2007 with merchant cash advances. Compared to a bank loan, almost all of these alternative options will be perceived as expensive, but if banks don’t approve anyone, then they’re a terrible standard for a comparison.

It’s taken a long time for the public and the media to come to terms with that. Banks are still technically in the game but by proxy. They are financing numerous alternative lenders and merchant cash advance companies. Banks shouldn’t be lending out their client’s deposits to really risky businesses anyway. A bank is supposed to be safe. If they’re lending money to 100 businesses and 15 of them aren’t paying it back, then that’s the opposite of safe.

So what do small businesses need banks for anyway? Checking, payroll, overdraft coverage, debit cards, wires, record keeping, CDs etc. There is a place for banks in 2013 and beyond. Alternative lenders charge more and that’s okay. Ultimately it’s up to the borrowers to decide what they can sustain. It is better to have expensive options than no options at all. There’s endless proof of that when credit dried up five years ago. Small businesses cried foul so the market reacted. And here we are now with Kabbage, On Deck Capital, Business Financial Services, and Capital Access Network being portrayed as the norm, the new standard. Almost everything that would cause a bank to say “no” can be resolved in some way. That’s incredible and how it should be.

So what do small businesses need banks for anyway? Checking, payroll, overdraft coverage, debit cards, wires, record keeping, CDs etc. There is a place for banks in 2013 and beyond. Alternative lenders charge more and that’s okay. Ultimately it’s up to the borrowers to decide what they can sustain. It is better to have expensive options than no options at all. There’s endless proof of that when credit dried up five years ago. Small businesses cried foul so the market reacted. And here we are now with Kabbage, On Deck Capital, Business Financial Services, and Capital Access Network being portrayed as the norm, the new standard. Almost everything that would cause a bank to say “no” can be resolved in some way. That’s incredible and how it should be.

People are finally getting it.

– Merchant Processing Resource

../../

MPR.mobi on your iPhone, Android, or iPad

¹ It took 5 years but Forbes has Finally deleted the March 13, 2008 article that haunted the merchant cash advance industry forever. In Look Who’s Making Coin off the Credit Crisis, Maureen Farrell referred to merchant cash advance companies as vampires that were feasting on small businesses and singled out some of the biggest names in the business at the time. It was Global Swift Funding* (GSF), one of the major funders cited by Farrell that exposed this assertion to be blatantly false. Not too long after the article was published, GSF closed their doors and filed for bankruptcy. It would seem that small businesses actually feasted on them by defaulting in record numbers. Back in April of this year, Forbes essentially rebuked that article when Cheryl Conner revisited the industry to note how much good it was doing in ‘Money, Money’ — How Alternative Lending Could Increase Your Company’s Revenue in 2013

*Disclosure: Raharney Capital, LLC the owner of this website currently owns the former domain of Global Swift Funding (GlobalSwiftFunding.com) though the companies did not have and do not have any ties to each other.

² IOU Central is a subsidiary of IOU Financial Inc. Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations as of August 22, 2013 are available at: http://cnsxmarkets.com/Storage/1563/144040_MDA_%282Q2013%29_-_FINAL.pdf

Merchant Cash Advance Contract Language

July 24, 2013 Below is a look back at some of the contract language used in the industry.

Below is a look back at some of the contract language used in the industry.

2009 First Funds Contract

Purchaser agrees to purchase from Seller and the Seller agrees to sell to Purchaser, in consideration of the purchase price specified below (the “Purchase Price”), Seller’s interest in the percentage specified below (the “Specified Percentage”) of each of its future credit card receivables (the “Future Receivables”) due to Seller from the credit card processor identified below (“Processor”) until the amount specified below (the “Specified Amount”) of Future Receivables has been collected by Purchaser according to the additional terms and conditions set forth in this Purchase and Sale Agreement (“Agreement”).

The undersigned principal(s) of Seller (such principals, whether shareholders, partners or other owners are referred to herein as the “Guarantor’) hereby unconditionally, jointly and severally, guarantee Seller’s performance and satisfaction of all the covenants, representations and warranties set forth in Section 3 of the Agreement. This guarantee is continuing and shall bind Guarantor’s heirs, successors and assigns, and may be enforced by or for the benefit of any assignee or successor of Purchaser. Purchaser shall not be obligated to take any action against the Seller prior to taking any action against the Guarantor. Guarantor shall pay Purchaser for all its overhead and expenses incurred in enforcing this guarantee and underlying Agreement, including all Purchaser’s reasonable attorney’s fees. The release and/or compromise of any obligation of Seller or any other obligors and guarantors shall not in any way release Guarantor from his or her obligations under this guarantee. This guarantee shall be governed and construed according to the laws of the State of New York. ALL ACTIONS, PROCEEDINGS OR LITIGATION RELATING TO OR ARISING FROM THIS GUARANTEE OR UNDERLYING AGREEMENT SHALL BE INSTITUTED AND PROSECUTED EXCLUSIVELY IN THE FEDERAL OR STATE COURTS LOCATED IN THE STATE AND COUNTY OF NEW YORK NOTWITHSTANDING THAT OTHER COURTS MAY HAVE JURISDICTION OVER THE PARTIES AND THE SUBJECT MATTER, AND GUARANTOR FREELY CONSENTS TO THE JURISDICTION OF THE FEDERAL OR STATE COURTS LOCATED IN THE STATE AND COUNTY OF NEW YORK. Service of process by certified mail to Guarantor’s address listed below or such other address that Guarantor may provide Purchaser in writing from time to time will be sufficient for jurisdictional purposes. GUARANTOR FREELY WAIVES, INSOFAR AS PERMITTED BY LAW, TRIAL BY JURY IN ANY ACTION, PROCEEDING OR LITIGATION ARISING FROM OR IN ANY WAY RELATING TO THIS GUARANTEE. GUARANTOR WAIVES, TO THE EXTENT PERMITTED BY APPLICABLE LAW, ANY RIGHT TO PURSUE A CLAIM AGAINST PURCHASER OR ITS ASSIGNS AS PART OF A CLASS ACTION, PRIVATE ATTORNEY GENERAL ACTION OR OTHER REPRESENTATIVE ACTION. Guarantor grants continued authority to Purchaser and its agents and representatives and any credit reporting agency employed by Purchaser to obtain Guarantor’s credit report and/or other investigative reports, and to investigate any references given or any other statements or data obtained from or about Guarantor or Seller or any of Seller’s principals for the purpose of this guarantee, Agreement or renewal thereof.

1. Methods of Collection; Use of Approved Processor.

Purchaser shall collect the cash attributable to the Specified Percentage in one of the following ways: (i) directly from Seller’s credit card processor; (ii) by debiting the Seller’s credit card processing deposit account or another of Seller’s accounts that has been approved by Purchaser; or (iii) by debiting an account established by the Seller with Purchaser’s approval specifically to hold funds that are due to Purchaser (“Dedicated Account”). Purchaser may decide in its sole discretion which of the three methods it will accept for the remittance of the Specified Percentage. If Purchaser elects to use method (i) or (ii), then Seller agrees to enter into an agreement with a credit card processor acceptable to Purchaser (“Approved Processor”). Purchaser reserves the right to change the collection method at any time, with five (5) days notice to Seller, if it is unable to collect funds on a consistent basis through the collection method initially selected.

1.1 Collection Directly from Processor.

If Purchaser agrees to accept the remittance of the Specified Percentage directly from the Seller’s Approved Processor, then Seller authorizes the Approved Processor to pay the Specified Percentage directly to Purchaser rather than to Seller until the Specified Amount has been received by the Purchaser from the Approved Processor. This authorization is irrevocable, absolute and unconditional. Seller further acknowledges and agrees that the Approved Processor will be acting on behalf of Purchaser to collect the Specified Percentage. Seller hereby irrevocably grants Approved Processor the right to hold the Specified Percentage and to pay Purchaser directly (at, before or after the time Approved Processor credits or remits to Seller the balance of the Future Receivables not sold by Seller to Purchaser) until the entire Specified Amount has been received by Purchaser. Seller acknowledges and agrees that the Approved Processor may provide Purchaser with Seller’s credit card, debit card and other payment card and instrument processing history, including without limitation Seller’s chargeback experience and any communications about Seller received by Approved Processor from a card processing system, as well as any other information Purchaser deems pertinent. Seller understands that Purchaser does not have any power or authority to control the Approved Processor’s actions with respect to the authorization, clearing, settlement and other processing of transactions and that Purchaser is not responsible for the Approved Processor’s actions. Seller agrees to hold Purchaser harmless for the Approved Processor’s actions or omissions.

1.2 Collection via ACH Withdrawals.

If Purchaser agrees to accept the remittance of the Specified Percentage by debiting the Seller’s credit card processing deposit account, then Seller (i) irrevocably authorizes the Approved Processor or their representative to provide daily reports to Purchaser regarding Seller’s credit card processing batch amounts, and (ii) irrevocably authorizes Purchaser, or its designated successor or assign to withdraw the Specified Percentages of the Future Receivables and any other amounts now due, hereinafter imposed, or otherwise owed in conjunction with this Agreement by initiating via the Automatic Clearing House (ACH) system debit entries to Seller’s account at the bank listed above or such other bank or financial institution that Seller may provide Purchaser with from time to time (“Bank Account”). In the event that Purchaser withdraws erroneously from the Bank Account, Seller authorizes Purchaser to credit the Bank Account for the amount erroneously withdrawn via ACH. Purchaser shall not be required to credit the Bank Account for amounts withdrawn related to credit card transactions which are subsequently reversed for any reason. Purchaser, in its sole discretion, may elect to offset any such amount from collections from Future Receivables. Seller represents that the Bank Account is established for business purposes only and not for personal, family, or household purposes. Seller understands that the foregoing ACH authorization is a fundamental condition to induce Purchaser to enter into this Agreement.

Before 2:00 P.M. EST of the day following each day that Seller conducts business, Seller shall cause Approved Processor or Approved Processor’s agent to deliver to Purchaser, in a format acceptable to Purchaser, a record from Approved Processor reflecting the total gross dollar amount of the preceding day’s credit card transactions processed by Approved Processor for Seller, irrespective of whether such amount consists of sales, taxes or other amounts collected by Seller from its customers (“Daily Batch Amount”). In the event that Seller is unable to procure Approved Processor’s compliance in a timely manner or as otherwise required under this section, within two (2) business days’ written notice by Purchaser to Seller of the same via facsimile to Seller at the fax number listed herein, Seller shall at its sole expense terminate its relationship with Approved Processor and exclusively engage the services of an alternative credit card processor that Purchaser approves in writing and enter into any merchant credit card processing agreement as the alternative credit card processor may require, which credit card processor shall thereafter be referred to and included within the meaning of “Approved Processor” herein. Alternatively, in the event of Approved Processor’s noncompliance, Purchaser is hereby authorized to estimate the Daily Batch Amount based upon Purchaser’s analysis of Seller’s historical experience and to collect the Specified Percentage of the Future Receivables as provided in Section 2 of this Agreement based upon such estimate. Purchaser will make appropriate adjustments upon the submission by Seller of statements with respect to the period of Approved Processor’s non-compliance. Further, Seller hereby irrevocably authorizes Purchaser to obtain information regarding its other bank account(s) from Approved Processor and/or from the sales agent, and to debit such bank account(s) in the event that Purchaser is unable to debit the Specified Percentage from Seller’s credit card processing account.

1.3 Collection from a Dedicated Account.

If Purchaser agrees to accept the remittance of the Daily Percentage by debiting a Dedicated Account, Seller agrees to complete all necessary forms to establish the Dedicated Account. Seller (i) irrevocably authorizes and will require Seller’s processor to deposit directly into the Dedicated Account a daily amount corresponding to Seller’s Daily Batch Amount multiplied by the Specified Percentage; and (ii) acknowledges and agrees that any funds deposited into the Dedicated Account by Seller’s processor will remain in the Dedicated Account until the Specified Percentage is withdrawn by Purchaser and then the remaining funds, minus any amount required to maintain the minimum balance for the account, will be forwarded to Seller’s Bank Account. If the Dedicated Account requires a minimum account balance, Purchaser may, in its sole discretion, fund the required minimum balance for the Dedicated Account out of the Purchase Price. Seller acknowledges and agrees that it shall not have the right to directly withdraw funds from the Dedicated Account.

2. Processing Trial; Commencement of Agreement. After this Agreement has been signed by Seller but prior to Purchaser’s acceptance, the parties shall conduct a processing trial of four or fewer business days in order to ensure that the Seller’s credit card transactions are being correctly processed through Approved Processor and that Purchaser timely receives the Daily Batch Amount in a satisfactory manner and format. Nothing herein shall create an obligation upon Purchaser to enter into this Agreement. The Agreement shall commence upon Purchaser’s payment to Seller of the Purchase Price.

3. Seller’s Covenants, Representations and Warranties. Seller and Guarantor represent, warrant and covenant the following as of this date and during the term of this Agreement:

a) Seller represents that it is not contemplating closing its business.

b) Seller represents that it has not commenced any case or proceeding seeking protection under any bankruptcy

or insolvency law, or had any such case or proceeding commenced against it, and it is not contemplating

commencing any such case or proceeding.

c) Seller represents that the Future Receivables are free and clear of all claims, liens or encumbrances of any

kind whatsoever.

d) Seller represents that it does not intend to temporarily close its business for renovations or other reasons

during the next twelve months.

e) Seller shall not take any action to discourage the use of credit cards which are settled through its processor or

to permit any event to occur which could have an adverse effect on the use, acceptance or authorization of credit cards for the purchase of Seller’s services and products;

f) Seller shall not change its arrangements with its credit card processor in any way which is adverse to Purchaser;

g) Seller shall not change the credit card processor through which the major credit cards are settled from Approved Processor to another credit card processor or to permit any event to occur that could cause a diversion of any of Seller’s credit card transactions to another processor without Purchaser’s prior written consent;

h) Seller represents that as of this date, all Seller’s credit card sales and transactions are being processed exclusively with Approved Processor or are being deposited exclusively into a Dedicated Account;

i) Seller shall not sell, dispose, convey or otherwise transfer its business or assets without the express prior written consent of Purchaser; Seller shall not enter into a concurrent agreement for the purchase and sale of future receivables with any purchaser aside from First Funds.

j) Seller shall furnish Purchaser with the bank statements for its Bank Account and any and all other accounts to which proceeds from Seller’s sales are deposited within seven (7) days’ of any such request by Purchaser;

k) Seller shall unconditionally ensure that the cash Seller receives from Approved Processor attributable to the

Specified Percentage of the Future Receivables is immediately thereafter available to Purchaser for collection

via ACH from Seller’s Bank Account;

l) Seller shall not attempt to revoke its ACH authorization to Purchaser set forth in this Agreement or otherwise

take any measure to interfere with Purchaser’s ability to collect the cash that Seller receives (i) from Approved Processor attributable to the Specified Percentage of the Future Receivables or (ii) from the Dedicated Account;

m) Seller shall not close its Dedicated Account, or close or change the bank account into which Approved Processor deposits the Future Receivables to another account without Purchaser’s prior written consent;

n) Seller shall not conduct its businesses under any name other than as disclosed to Purchaser or change any of its places of business without Purchaser’s prior written consent; and

o) Seller represents that the information it furnished Purchaser in this Agreement and preceding application, including without limitation, Seller’s processing statements, is true and accurate in all respects and fairly represents the financial condition, result of operations and cash flows of Seller at such dates, and since the dates therein, there has been no material adverse change in the business or its prospects or in the financial condition, results of operations, or cash flows of Seller.

4. Agency; Modifications & Amendments; Entire and Final Agreement. Purchaser does not have any power or authority or control over Approved Processor’s actions with respect to the processing of Seller’s credit card transactions. Purchaser is an entirely separate and independent entity from the Processor and ISO (if any) and their respective agents. Neither Approved Processor nor ISO (if any) is Purchaser’s agent and neither is authorized to waive or alter any term or condition of this Agreement and their representations shall in no way affect Seller’s or Purchaser’s rights and obligations set forth herein. This Agreement contains the entire and final expression of the agreement between the parties, and may not be waived, altered, modified, revoked or rescinded except by a writing signed by one of Purchaser’s executive officers. All prior and/or contemporaneous oral and written representations are merged herein. No attempt at oral modification or rescission of this Agreement or any term thereof will be binding upon the parties.

5. Governmental Approvals. Seller possesses and is in compliance with all permits, licenses, approvals, consents and other authorizations necessary to own, operate and lease its properties and to conduct the business in which it is presently engaged. Seller is in compliance with any and all applicable federal, state, and local laws and regulations, including, without limitation, all laws and regulations relating to the prosecution of the confidentiality of information received from credit card users.

6. Exclusive Use of Processor. Seller understands that services of Approved Processor are the exclusive means by which Seller may process its credit card transactions, unless it has set up a Dedicated Account, in which case all of Seller’s credit card processing must be subject to daily withholding of the Specified Percentage in the Dedicated Account.

7. Sale of Future Receivables; Non-Consumer Transaction. Seller and Purchaser agree that the Purchase Price paid by Purchaser in exchange for the Specified Amount of Future Receivables is for the purchase and sale of the Specified Amount of Future Receivables and is not intended to be, nor shall it be construed as, a loan or an assignment for security from Purchaser to the Seller. Seller and Guarantor hereby acknowledge and agree that neither party is a “consumer” with respect to this Agreement and underlying transaction, and neither this Agreement nor any guarantee thereof shall be construed as a consumer transaction.

8. No Right to Repurchase. Seller acknowledges that it has no right to repurchase the Specified Amount of Future Receivables from Purchaser.

9. Sale of Additional Future Receivables; Schedules; Right of First Refusal. Nothing herein shall obligate either party to sell and purchase future credit card receivables; however, Seller grants Purchaser the right of first refusal to purchase any such additional future credit card receivables that Seller may wish to sell during the term of this Agreement and during the period ending ninety (90) days after termination of this Agreement. Under such right of first refusal, if Seller desires to sell additional future credit card receivables, Seller agrees to sell such receivables to Purchaser only, and not to any other prospective purchaser, so long as Purchaser purchases such future credit card receivables on terms that are no less favorable to Seller as the terms and conditions of this Agreement.

10. Default. A “Default” shall include, but not be limited to, any of the following events: (a) The breach by Seller of any covenants contained in this Agreement; (b) Any representation or warranty made by the Seller in this Agreement, proving to have been incorrect, false or misleading in any material respect.

11. Remedies. In the event of a Default, Purchaser shall be entitled to all remedies available under law. Without limiting the generality of the foregoing, in the event of Seller’s default under Section 10 herein, Purchaser will be entitled to require Seller to purchase the remaining Future Receivables for an amount equal to the amount by which the Specified Amount of Future Receivables exceeds the amount of cash received from Future Receivables that Purchaser had previously collected under this Agreement, which amount Purchaser may automatically debit from Seller’s Bank Account via ACH without notice to Seller. No failure on the part of Purchaser to exercise, nor any delay in exercising any right under this Agreement shall operate as a waiver thereof, nor shall any single or partial exercise of any right under this Agreement preclude any other or further exercise of any other right. The remedies provided hereunder are cumulative and not exclusive of any remedies provided by law or equity.

12. UCC-1 Financing Statements. Seller authorizes Purchaser to file one or more UCC-1 Financing Statements prior to each sale of Future Receivables for purposes of providing public notice of the purchase by Purchaser from Seller of the Specified Amount of Future Receivables. The UCC-1 Financing Statements will state that the sale of the Future Receivables is an outright sale and not an assignment for security.

13. Notices. All notices, requests, demands and other communications hereunder, including disputes or inaccuracies concerning information furnished to credit reporting agencies shall be, unless otherwise provided herein, in writing and shall be delivered by mail, overnight delivery or hand delivery to the respective parties to this Agreement at their respective addresses listed on the face of this Agreement or at such other address that either may provide to the other in writing from time to time.

14. Binding Effect; Assignment. This Agreement shall be binding upon and inure to the benefit of Seller, Purchaser and their respective successors and assigns, except that Seller shall not have the right to assign its rights hereunder or any interest herein without the prior written consent of Purchaser which consent may be withheld at Purchaser’s sole discretion. Purchaser may assign this Agreement without notice to Seller.

15. Governing Law and Jurisdiction. This Agreement shall be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of the State of New York. Seller consents to the jurisdiction of the federal and state courts located in the State and County of New York and agrees that such courts shall be the exclusive forum for all actions, proceedings or litigation arising out of or relating to this Agreement or subject matter thereof, notwithstanding that other courts may have jurisdiction over the parties and the subject matter thereof. Service of process by certified mail to Seller’s address listed on the face of this Agreement will be sufficient for jurisdictional purposes.

16. Purchaser’s Costs of Enforcement; Attorney’s Fees. Purchaser shall be entitled to receive from Seller and Seller shall pay to Purchaser, all Purchaser’s costs and expenses, including Purchaser’s collections overhead and Purchaser’s reasonable attorney’s fees, in enforcing any of the terms of this Agreement, regardless of whether or not a legal action has been commenced. If Seller files action against Purchaser and the matter is dismissed or Purchaser prevails in the matter, Seller agrees to pay all of Purchaser’s attorney fees and costs incurred whether in court or arbitration.

17. Severability. In case any one or more of the provisions contained in this Agreement should be invalid, illegal or unenforceable in any respect, the validity legality and enforceability of the remaining provisions contained herein and therein shall not in any way be affected or impaired thereby.

18. Limitation of Liability. In no event will Purchaser be liable for any claims asserted by Seller under any theory of law, including any tort or contract theory for lost profits, lost revenues, lost business opportunities, exemplary, punitive, special, incidental, indirect or consequential damages, each of which is hereby expressly waived to the fullest extent permitted by law by Seller.

19. Waiver Of Jury Trial; Limitation On Action. PURCHASER AND SELLER KNOWINGLY, WILLINGLY AND VOLUNTARILY WAIVE, INSOFAR AS PERMITTED BY LAW, TRIAL BY JURY IN ANY ACTION, PROCEEDING OR LITIGATION BROUGHT BY PURCHASER, SELLER OR GUARANTOR HERETO ARISING FROM OR IN ANY WAY RELATING TO THIS AGREEMENT OR THE UNDERLYING TRANSACTION. SELLER SHALL COMMENCE ANY ACTION OR COUNTERCLAIM BASED IN CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE ARISING FROM OR IN ANY WAY RELATING TO THIS AGREEMENT OR THE UNDERLYING TRANSACTION WITHIN ONE YEAR OF THE ACCRUAL OF THAT CAUSE OF ACTION AND NO SUCH ACTION MAY BE MAINTAINED WHICH IS NOT COMMENCED WITHIN THAT PERIOD. SELLER KNOWINGLY, WILLINGLY AND VOLUNTARILY WAIVES, TO THE EXTENT PERMITTED BY APPLICABLE LAW, ANY RIGHT TO PURSUE A CLAIM AGAINST PURCHASER AS PART OF A CLASS ACTION, PRIVATE ATTORNEY GENERAL ACTION OR OTHER REPRESENTATIVE ACTION.

—————–

2006 AdvanceMe Contract

In exchange for payment by Company to Merchant of the purchase price specified below (“Purchase Price”), Company hereby purchases from Merchant and Merchant hereby sells to Company all of Merchant’s right, title and interest in and to the amount specified below (“Specified Amount”) of Merchant’s future receivables (“Future Receivables”) arising from payments by Merchant’s customers with cards (“Cards”) of a type settled, directly or indirectly, by Processor (as defined below). Merchant will remit the Specified Amount of Future Receivables to Company by causing a processor acceptable to Company (“Processor”) to pay Company each day an amount of cash equal to the percentage specified below (“Specified Percentage”) of all Card receivables due to Merchant on the day in question (“Receivables”). Company will continue to receive the Specified Percentage of Receivables until Merchant has remitted to Company the entire Specified Amount of Future Receivables.

Company will not increase the Specified Percentage without Merchant’s prior written consent. Merchant (i) will enter into an agreement acceptable to Company with Processor to obtain processing services (“Processing Agreement”) and (ii) hereby authorizes Processor and/or Operator (as defined below) to pay daily the cash attributable to the Specified Percentage of Receivables to Company rather than to Merchant and to debit the Account (as defined below) in such amounts until Company receives the cash attributable to the entire Specified Amount of Future Receivables.

Merchant agrees (i) to conduct its business consistent with past practice; (ii) to exclusively use Processor for the processing of all of its Card transactions, to not change its arrangements with Processor in any way that is adverse to Company and to not take any action that has the effect of causing the processor through which Cards are settled to be changed from Processor to another processor; (iii) to not take any action to discourage the use of Cards and to not permit any event to occur that could have an adverse effect on the use, acceptance or authorization of Cards for the purchase of Merchant’s services and/or products; (iv) to not open a new account other than the Account to which Card settlement proceeds will be deposited and to not take any action to cause Future Receivables or Receivables to be settled or delivered to any account other than the Account; (v) not to sell, dispose, convey or otherwise transfer its business or assets without the express prior written consent of Company and the assumption of all of Merchant’s obligations under this Agreement pursuant to documentation reasonably satisfactory to Company; and (vi) to maintain a Minimum Balance (as defined below) in the Account (collectively, the “Merchant Contractual Covenants”).

The owners of Merchant (such owners, whether shareholders, partners, members or other owners are referred to herein as “Owners”) hereby guarantee the performance of all of the covenants made by Merchant in this Agreement, including the Merchant Contractual Covenants.

To the extent set forth herein, each of the parties is obligated upon his, her or its execution of the Agreement to all terms of the Agreement, including the Additional Terms set forth below. Each of above-signed Merchant and Owner(s) represents that he or she is authorized to sign this Agreement for Merchant and that the information provided herein and in all of Company’s forms is true, accurate and complete in all respects. If any such information is false or misleading, Merchant shall be deemed in material breach of all agreements between Merchant and Company and Company shall be entitled to all remedies available under law. Company may produce a monthly statement reflecting the delivery of the Specified Percentage of Receivables from Merchant via Processor and/or Operator. Merchant hereby agrees to a $___ administrative fee per month for the production of the monthly statement and further agrees that Company and its designees may debit such administrative fee from Merchant’s bank account each month via the automated clearing house (“ACH”) system. An investigative or consumer report may be made in connection with the Agreement. Merchant and each of the above- signed Owners authorizes Company, its agents and representatives and any credit reporting agency engaged by Company, to (i) investigate any references given or any other statements or data obtained from or about Merchant or any of its Owners for the purpose of this Agreement, and (ii) pull credit reports at any time now or for so long as Merchant and/or Owner(s) continue to have any obligation owed to Company as a consequence of this Agreement or for Company’s ability to determine Merchant’s eligibility to enter into any future agreement with Company.

I. PROCESSING TERMS AND ARRANGEMENTS.

Section 1.1. Processing Agreement. Merchant understands and agrees that the Processing Agreement and the authorizations to debit set forth above irrevocably authorize Processor and Operator to pay the cash attributable to the Specified Percentage of Receivables to Company rather than to Merchant until Company receives the cash attributable to the entire Specified Amount of Future Receivables from Processor and/or Operator. These authorizations may be revoked only with the prior written consent of Company. Merchant agrees that Processor and Operator may rely upon the instructions of Company, without any independent verification, in making the cash payments described above. Merchant waives any claim for damages it may have against Processor or Operator in connection with actions taken based on instructions from Company, unless such damages were due to such Processor’s or Operator’s failure to follow Company’s instructions. Merchant acknowledges and agrees that (a) Processor and Operator will be acting on behalf of Company with respect to the Specified Percentage of Receivables until the cash attributable to the entire Specified Amount of Future Receivables has been remitted by Processor and/or Operator to Company, (b) Processor and Operator may or may not be affiliates of Company, (c) Company does not have any power or authority to control Processor’s or Operator’s actions with respect to the processing of Card transactions or remittance of cash to Company, and (d) Company is not responsible for, and Merchant agrees to hold Company harmless for, the actions of Processor and Operator. For purposes of this Agreement, the term “Operator” shall mean any party Company designates to debit any amounts from Merchant’s or Owners’ accounts as authorized or permitted by this Agreement.

Section 1.2. Instructions to Processor. Merchant will irrevocably instruct Processor to hold the Specified Percentage of Receivables on behalf of Company and to remit directly to Company the cash attributable thereto at the same time it remits to Merchant the cash attributable to the balance of the Receivables. Merchant acknowledges and agrees that Processor shall provide Company with Merchant’s Card transaction history.

Section 1.3. Indemnification. Merchant indemnifies and holds each of Processor and Operator, their respective officers, directors, affiliates, employees, agents and representatives harmless from and against all losses, damages, claims, liabilities and expenses (including reasonable attorneys’ fees) suffered or incurred by Processor or Operator resulting from actions taken by Processor or Operator in reliance upon information or instructions provided to Processor or Operator by Company.

Section 1.4. Limitation of Liability. In no event will Processor, Operator or Company be liable for any claims asserted by Merchant under any theory of law, including any tort or contract theory for lost profits, lost revenues, lost business opportunities, exemplary, punitive, special, incidental, indirect or consequential damages, each of which is hereby expressly waived by Merchant.

Section 1.5. Processor Commissions. Merchant understands and agrees that Processor will charge a fee or commission for processing receipts of Receivables (the “Processor’s Fee”) as set forth in the Processing Agreement and that the Processor’s Fee will be deducted from the portion of the Receivables payable to Merchant and not from the cash attributable to the Specified Percentage of Receivables payable to Company.

Section 1.6. No Modifications. Merchant will comply with the Processing Agreement and will not modify the Processing Agreement in any manner that could have an adverse effect upon Company’s interests, without Company’s prior written consent.

Section 1.7. Account. Merchant represents and warrants that Merchant’s sole bank account (“Account”) into which all settlement proceeds of Receivables will be deposited is that account identified by account name, account number and bank name and address that is shown on the face of the voided check that Merchant shall provide to Company along with this Agreement, the delivery of which voided check is a condition precedent to Company’s obligations under this Agreement. If Processor transfers to the Account or any other account of Merchant or Owner(s) any funds that should have been transferred to Company pursuant to Sections 1.1 and 1.2 hereof, or if Merchant otherwise has monies deposited in its or Owner(s)’s account(s) that otherwise should have been transferred to Company pursuant to Sections 1.1 and 1.2 hereof, Merchant shall immediately segregate and hold all such funds in express trust for Company’s sole and exclusive benefit. In any such circumstance, Merchant shall maintain in the Account a minimum balance equal to Company’s undivided interest in such funds or the Specified Percentage multiplied by the Merchant’s average daily Card volume based on the processing records provided to Company prior to the execution of this Agreement (assuming twenty-one days of processing per month) multiplied by three (3), whichever is greater (“Minimum Balance”), until such funds are paid to Company. Merchant and each Owner authorizes Company, Processor and Operator to debit such funds directly from all such accounts, including the Account, and agrees to not revoke or cancel such authorizations until such time as Company has received the entire Specified Amount of Future Receivables. Merchant acknowledges and agrees that Company, Processor and Operator may issue a pre-notification to Merchant’s and/or Owner(s)’s bank(s) with respect to such debit transactions. Within twenty-four (24) hours of any request by Company, Merchant shall provide, or cause Processor or Operator to provide, Company with records and other information regarding Merchant’s Card sales, the Account and any other accounts of Merchant or Owner(s).

Section 1.8. Processing Trial. After this Agreement has been signed by both Merchant and Company but prior to Company’s determination as to whether to pay the Purchase Price, Merchant agrees to permit Company to instruct Processor and/or Operator to conduct a short processing trial (the “Processing Trial”) to ensure that Merchant’s Card transactions are being correctly processed through Processor and that the cash attributable to the Specified Percentage of Receivables will be appropriately remitted to Company. Company agrees to make a determination as to whether to purchase the Specified Amount of Future Receivables promptly after the commencement of the Processing Trial. If Company elects to purchase the Specified Amount of Future Receivables, then all of the cash received by Company in connection with the Processing Trial prior to the payment of the Purchase Price shall be applied to reduce the Specified Amount. Nothing herein shall create an obligation on behalf of Company to purchase any Future Receivables, and Company expressly reserves the right to not purchase the Specified Amount of Future Receivables and not pay the Purchase Price to Merchant. If Company decides to not purchase the Specified Amount of Future Receivables and not pay the Purchase Price, this Agreement shall have no further effect and Company shall, promptly after receipt from Processor or Operator, return to Merchant any cash received by Company in connection with the Processing Trial.

Section 1.9. Excess Cash. In the event that the amount of cash remitted to Company pursuant to this Agreement exceeds the Specified Amount (such excess being the “Excess Cash”) by at least $20.00, Company agrees to pay such Excess Cash to Merchant within thirty (30) days after receipt thereof by Company. In the event the Excess Cash is less than $20.00, Company agrees to pay such Excess Cash to Merchant within thirty (30) days after its receipt of a written request from Merchant, provided such request is made within six months of Company’s receipt of such Excess Cash. Merchant acknowledges and agrees that Company has no obligation to take any action (including against Processor or Operator) with respect to any cash being held by Processor or Operator, which will become Excess Cash once it is paid by Processor or Operator to Company, prior to the receipt of such Excess Cash by Company.

Section 1.10. Reliance on Terms. The provisions of this Agreement are agreed to for the benefit of Merchant, Owner(s), Company, Processor and Operator and, notwithstanding the fact that Processor and Operator are not parties to this Agreement, they may rely upon the terms of this Agreement and raise them as defenses in any action.

II. REPRESENTATIONS, WARRANTIES AND COVENANTS.

Merchant and Owner(s) represent, warrant and covenant the following as of the date hereof and during the term of this Agreement:

Section 2.1. Merchant Contractual Covenants. Merchant shall comply with each of the Merchant Contractual Covenants as set forth herein.

Section 2.2. Business Information. All information (financial and other) provided by or on behalf of Merchant to Company in connection with the execution of or pursuant to this Agreement is true, accurate and complete in all respects. Merchant shall furnish Company, Processor and Operator such information as Company may request from time to time.

Section 2.3. Reliance on Information. Merchant acknowledges and agrees that all information (financial and other) provided by or on behalf of Merchant has been relied upon by Company in connection with its decision to purchase the Specified Amount of Future Receivables.

Section 2.4. Compliance. Merchant is in compliance with any and all applicable federal, state and local laws and regulations and rules and regulations of card associations and payment networks. Merchant possesses and is in compliance with all permits, licenses, approvals, consents, registrations and other authorizations necessary to own, operate and lease its properties and to conduct the business in which it is presently engaged.

Section 2.5. Authorization. Merchant and the person(s) signing this Agreement on behalf of Merchant have full power and authority to enter into and perform the obligations under this Agreement and the Processing Agreement, all of which have been duly authorized by all necessary and proper actions.

Section 2.6. Insurance. Merchant shall maintain insurance in such amounts and against such risks as are consistent with past practice and shall show proof of such insurance upon the request of Company. Section 2.7. Change Name or Location. Merchant does not and shall not conduct Merchant’s business under any name other than as disclosed to Company and Processor and shall not change its place of business.

Section 2.8. Merchant Not Indebted to Company. Merchant is not a debtor of Company as of the date of this Agreement.

Section 2.9. Exclusive Use of Processor. Merchant understands and agrees that the services of Processor are the exclusive means by which Merchant can and shall process its Card transactions.

Section 2.10. Working Capital Funding. Merchant shall not enter into any arrangement, agreement or commitment that relates to or involves Future Receivables, whether in the form of a purchase of, a loan against, or the sale or purchase of credits against, Future Receivables or future Card sales with any party other than Company.

Section 2.11. Unencumbered Future Receivables. Merchant has good, complete and marketable title to all Future Receivables, free and clear of any and all liabilities, liens, claims, charges, restrictions, conditions, options, rights, mortgages, security interests, equities, pledges and encumbrances of any kind or nature whatsoever or any other rights or interests that may be inconsistent with the transactions contemplated with, or adverse to the interests of, Company.

Section 2.12. Business Purpose. Merchant is a valid business in good standing under the laws of the jurisdictions in which it is organized and/or operates, and Merchant is entering into this Agreement for business purposes and not as a consumer for personal, family or household purposes.

III. ADDITIONAL TERMS.

Section 3.1. Sale of Future Receivables. Merchant and Company agree that the Purchase Price paid by Company in exchange for the Specified Amount of Future Receivables is a purchase of the Specified Amount of Future Receivables and is not intended to be, nor shall it be construed as, a loan or financial accommodation from Company to Merchant.

Section 3.2. No Right Merchant acknowledges and agrees that it has no right to repurchase the Specified Amount of Future Receivables from Company and Company may not force Merchant to repurchase the Specified Amount of Future Receivables.

Section 3.3. Remedies. In the event that any of the representations or warranties contained in this Agreement is not true, accurate and complete, or in the event of a breach of any of the covenants contained in this Agreement, including the Merchant Contractual Covenants, Company shall be entitled to all remedies available under law, including the right to non-judicial foreclosure. In the event that Merchant breaches any of the Merchant Contractual Covenants specified in clauses (ii) or (iv) on the first page of this Agreement, Merchant agrees that Company shall be entitled to, but not limited to, damages equal to the amount by which the cash attributable to the Specified Amount of Future Receivables exceeds the amount of cash received from Receivables that have previously been delivered by Merchant to Company pursuant to this Agreement. Merchant hereby agrees that Company and Operator may automatically debit such damages from Merchant’s bank accounts via the ACH system or wire transfers. The obligations of Owners, including the guarantee on the first page of this Agreement are primary and unconditional and each Owner waives any rights to require Company to first proceed against Merchant.

Section 3.4. Financing Statements. To secure performance of the Merchant Contractual Covenants and all of the other obligations of Merchant to Company under this Agreement or any other agreement between Merchant and Company, Merchant grants to Company a continuing priority security interest, subject only to the security interest of Processor, if any, in the following property of Merchant wherever found: (a) All personal property of Merchant, including, all accounts, chattel paper, documents, equipment, general intangibles, instruments, inventory (as those terms are defined in Article 9 of the Uniform Commercial Code (“UCC”) in effect from time- to-time in the State of New York), and liquor licenses, wherever located, now or hereafter owned or acquired by Merchant; (b) all trademarks, trade names, service marks, logos and other sources of business identifiers, and all registrations, recordings and applications with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) and all renewals, reissues and extensions thereof (collectively “IP”) whether now owned or hereafter acquired, together with any written agreement granting any right to use any IP; and (c) all proceeds with respect to the items described in (a) and (b) above, as the term “proceeds” is defined in Article 9 of the UCC. Merchant understands and agrees that Company may file one or more (i) UCC-1 financing statements at anytime to perfect the interest created under the UCC upon the sale, and (ii) assignments with USPTO to perfect the security interest in IP described above. The UCC-1 financing statements may state that the sale of the Specified Amount of Future Receivables is intended to be a sale and not an assignment for security.

Section 3.5. Protection of Information. Merchant and each person signing this Agreement on behalf of Merchant and/or as Owner, in respect of himself or herself personally, authorizes Company to disclose to any third party information concerning Merchant’s and each Owner’s credit standing (including credit bureau reports that Company obtains) and business conduct. Merchant and each Owner hereby waives to the maximum extent permitted by law any claim for damages against Company or any of its affiliates relating to any (i) investigation undertaken by or on behalf of Company as permitted by this Agreement or (ii) disclosure of information as permitted by this Agreement.

Section 3.6. Solicitations. Merchant and each Owner authorizes Company and its affiliates to communicate with, solicit and/or market to Merchant and each Owner via regular mail, telephone, email and facsimile in connection with the provision of goods or services by Company, its affiliates or any third party that Company shares, transfers, exchanges, discloses or provides information with or to pursuant to Section 3.5 and will hold Company, its affiliates and such third parties harmless against any and all claims pursuant to the federal CAN-SPAM ACT of 2003 (Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing Act of 2003), the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA), and any and all other state or federal laws relating to transmissions or solicitations by any of the methods described above.

Section 3.7. Confidentiality. Merchant understands and agrees that the terms and conditions of the products and services offered by Company, including this Agreement and any other Company documentation (collectively, “Confidential Information”) are proprietary and confidential information of Company. Accordingly, unless disclosure is required by law or court order, Merchant shall not disclose Confidential Information to any person other than an attorney, accountant, financial advisor or employee of Merchant who needs to know such information for the purpose of advising Merchant (“Advisor”), provided such Advisor uses such information solely for the purpose of advising Merchant and first agrees in writing to be bound by the terms of this Section 3.7).

Section 3.8. Publicity. Merchant and each Owner authorizes Company to use its, his or her name in a listing of clients and in advertising and marketing materials.

IV. MISCELLANEOUS.